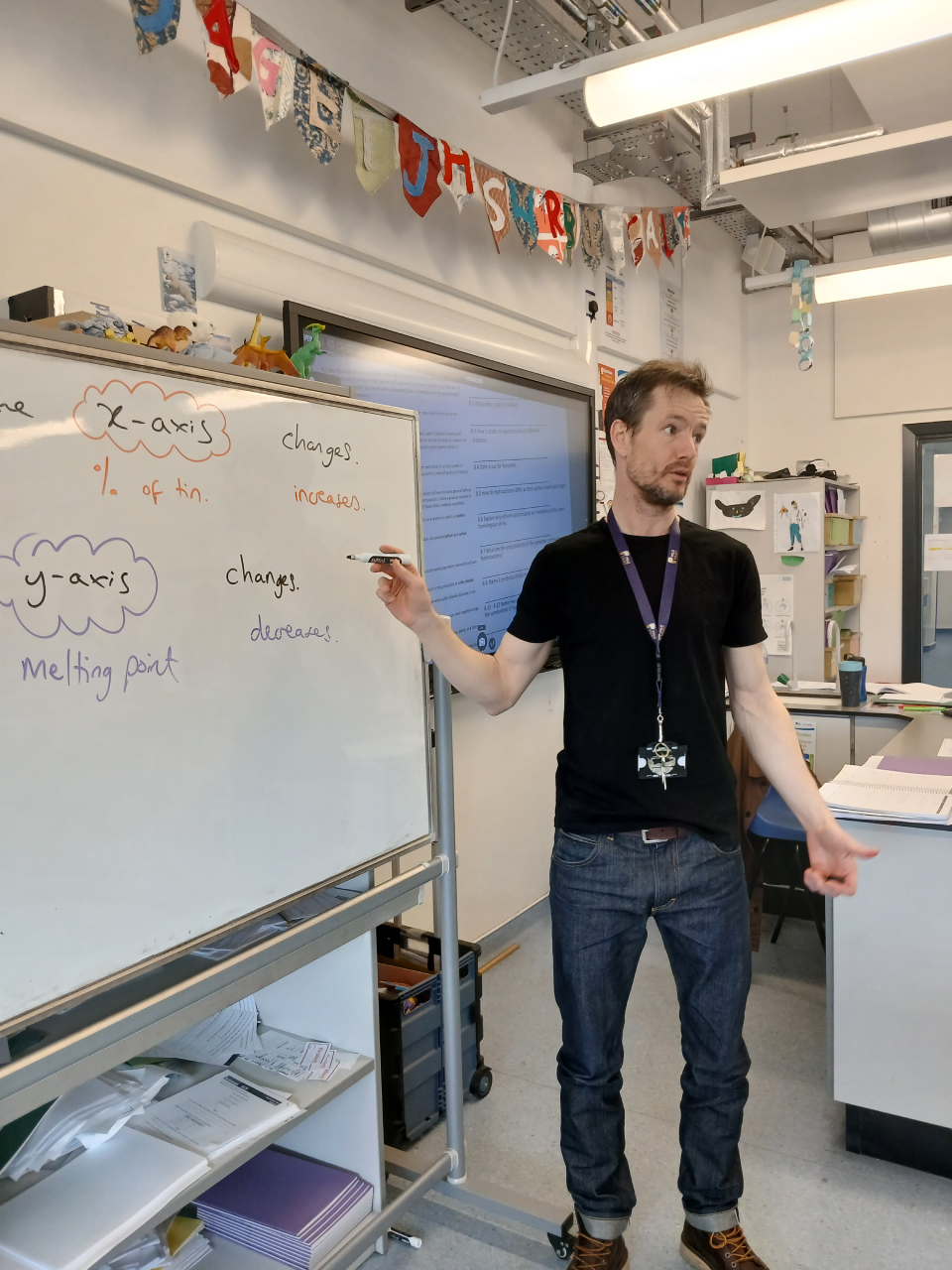

“The fact that I’m a teacher I owe to Life.” Lee Patterson, secondary school science teacher

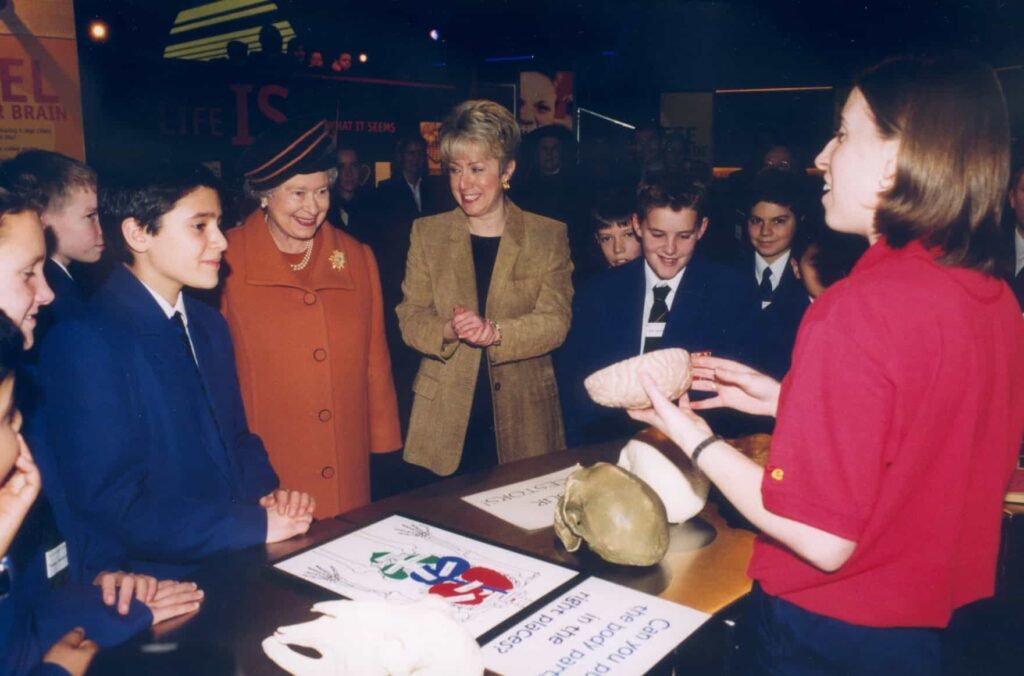

Lee Patterson started working at Life part time while studying Environmental Science.

In his role as a science explainer, he worked with young people who visited the science centre, engaging them in activities, bringing science to life, and hopefully igniting their enthusiasm for the subject.

Shortly after he graduated, he took on a more senior position as a lab supervisor, and stayed with Life for five years.

“Over those five years I worked with thousands of children from hundreds of schools,” Lee says, “and my love of working with children really grew from there.”

Life’s then head of education Noel Jackson first spotted Lee’s aptitude for teaching.

“He said ‘do you think you’re as good as the people that come in here?’,” Lee remembers, “and we had a bit of a laugh and I said, ‘well sometimes I think I’m a bit better than them!’ And Noel talked about the need for skilled science communicators within science education.”

Inspired by that conversation, Lee reached out to the teacher training programme at Newcastle University and started a new phase in his career.

He has now been a science teacher for 11 years.

“Working at Life gave me the skills, the confidence and actually the desire to take what was informal education and make it more formal.”

Moving into formal science education, Lee realised how key the skills he developed at Life were: the confidence in delivering science materials; the ability to make lessons fun and engaging.

Lee is a local lad who grew up in Wallsend, went to Newcastle University and now teaches in North Shields. He is passionate about connecting people in the region with science.

He explains how his experience at Life shaped him into being a teacher, without the pressure of the classroom.

“The education department would bring groups of school children on weekdays and do workshops with them,” he remembers. “My responsibility was to take the schedule and make sure all the equipment was prepared, manage the other science explainers and make sure everybody knew what they were doing when.

“If you had a big workshop that might have required some preparation three or four days in advance,” Lee continues. “Bacterial cultures, organise all that. It was fun, it was varied. No two days were ever the same.”

He was given the freedom to explore, whether that was designing new sessions or having a go at making things from scratch. A series on the science of sound had a particular impact on him, triggering him to first pick up a guitar. He still plays today.

“By the time I left Life, I’d become quite a prolific maker,” Lee says. “I still do hobby electronics. I’ve made my own guitar amps, my own wah-wah pedals. These are all things I picked up working there, making things for the department.”

That spirit of enthusiasm and unrestricted exploration is something Lee finds can be missing in traditional science education.

“Nobody could have predicted when we were kids that programming would have been such a boom business. We don’t even know what opportunities are going to be afforded to people in the future, but they will be based around scientific knowledge.”

It can be difficult to break out of the classroom, especially at secondary level, where doing so disrupts other teachers and lessons, but Lee makes regular visits to Life with his school’s science club.

“The impact it has on children is massive,” Lee says, “especially opening their eyes to what a science degree might be like in a high-end lab space, with equipment they’d never get a sample of in a state-run school.”

“Giving that opportunity to children, especially from the area we’re in, helps them decide if that’s the path they want to take,” he continues.

It goes beyond higher education and careers, however.

Driven by his love of science communication, Lee is his school’s oracy lead, focused on improving students’ oral language and communication skills. He believes he’s the only science teacher in North Tyneside to hold a responsibility which more commonly sits with English teachers.

He says, “I’m focused on: how do you communicate what you want to communicate accurately?”

He sets this against the typically more persuasive or poetic approach taken in English as a subject.

For Lee, good science communication is linked with navigating the modern world.

“The reason science communication is even more important now than it ever has been, is the problems we face can only be fixed through technological and scientific solutions,” Lee argues.

“Science education in general teaches you to be cynical and to question what you’re told,” he continues. “I’m always telling children that if you’re not scientifically literate, you’re just gonna have to accept that for the rest of your life you’re going to be manipulated and people are going to tell you things and you’re not going to have the tools you need to analyse what you’re being told!”